Um forgettable… that’s what you are.

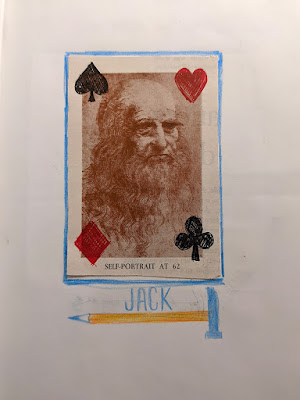

I consider myself exceptionally medium (except for hat sizes). Which is to say not big or small (unless I’m in Oklahoma), not virtuoso nor dunce. A jack of all trades moving along before mastering. An unmemorable renaissance man. A serial hobbyist. We tend to glorify the specialist be they painter, baseball player or cellist. The only jack of all trades standing the test of history that I can think of is Leonardo da Vinci (warrants further research).

I consider myself exceptionally medium (except for hat sizes). Which is to say not big or small (unless I’m in Oklahoma), not virtuoso nor dunce. A jack of all trades moving along before mastering. An unmemorable renaissance man. A serial hobbyist. We tend to glorify the specialist be they painter, baseball player or cellist. The only jack of all trades standing the test of history that I can think of is Leonardo da Vinci (warrants further research).

By definition medium is “about halfway between two extremes of size or another quality; average.” At the same time it is also “an agency or means of doing something.” By that definition creativity cannot become tangible without a medium. So perhaps medium is not forgettable, but integral.

This digressive opening is a means of discussing medium scale bass guitars. I’ve been playing medium scale (32”) basses for the last six years. I arrived there I suppose by definition as it was about halfway between the extremes. Like most bass guitarists I started on long scale and then for purposes of style moved to a short scale semi-hollow. Sonically, I reached the decision that short scale lacked a certain something (overtones). I then switched over to a long scale fretless acoustic.

I stumbled across medium scale at some point in 2015. Having discovered something new (to me) I ascribed it with silver bullet status. Not in the south-midwesterners response to Miller Light (Coors Light) kind of way, but in the single means of killing a werewolf. A sonic werewolf. At that time silver bullets seemed to be in limited supply.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say limited at a low price point. I found the Fender T Bucket and the Ibanez PCBE12MH. Although it wouldn’t matter in the case of that particular instrument (chapter two) the Ibanez’s simple, “open pore” finish was more appealing to me. I also couldn’t find the T Bucket anywhere. In the world of guitars it always seemed to me that there are two camps: Gibson and Fender. I’ve always considered myself in the Fender camp, but as it turns out I’m really in the Ibanez camp. Not being a guitar shredder or having much interest in that music nor being of Japanese descent which would suggest a patriotic alliance, I’m not sure what that camp says about me. As it stands today though: Ibanez 4, Fender 1 1/2.

There isn’t any exceptionally logical reason to have four very similar instruments other than it provides entertainment in the building and they’ve all been customized as means to different ends. Over the last few years I haven’t been performing as much and when I do the shows have been smaller and more acoustic. In this environment the acoustic quality of the AGB can really shine. However Brenda, my first Ibanez wasn’t built with that intention.

FULL CUSTOM FAILURE

I set out to build a more acoustic, acoustic bass guitar. After eight months of off and on building from scratch my result was a bit of a let down. Part of this was due to not sticking to the original plan and part of it was due to inexperience. A vital lesson that is hard to learn—knowing when it’s better to start over than to continue on.

FULL CUSTOM FAILURE

I set out to build a more acoustic, acoustic bass guitar. After eight months of off and on building from scratch my result was a bit of a let down. Part of this was due to not sticking to the original plan and part of it was due to inexperience. A vital lesson that is hard to learn—knowing when it’s better to start over than to continue on.

In July of 2021 I decided I should simply look for another Ibanez to modify. In August and September that’s just what I did. I really like the playability of the Ibanez PCBE12MH and it is a darn cheap guitar. New, you can fetch one for about $250 and there are many used available under $200. My argument is that this (low cost) makes it a fantastic starting point. For one, a ton of build time is saved—easily worth 200 bones. Being affordable means there is some oversight on the details. So, you’ll begin by smoothing the fret edges (if you keep them) then moving on to swapping hardware. From there you may want to work on the finish, adjust electronics or change out the pickguard.

My first intention was to keep this customization pretty simple. Over the last couple of years I’ve become more and more intrigued by antiqued finishes in the violin family vernacular. Think distressing or “relic-ing” in a more sophisticated or perhaps restrained way. So I wanted to experiment with that some. Here’s a look at what I did.

THE NECK

Having done this a few times, I like to start with the neck—in this case removing the frets. While it is mythologized that when Jaco Pastorius materialized into physical form from the ether, he found a jazz bass in a pawn shop and then plucked the frets off with a pocket knife before coating the fingerboard with marine grade epoxy, I recommend using a fret puller. I did it the Jaco-way the first couple times around and it works, although it adds a little danger and increases potential damage to the fingerboard.

Having done this a few times, I like to start with the neck—in this case removing the frets. While it is mythologized that when Jaco Pastorius materialized into physical form from the ether, he found a jazz bass in a pawn shop and then plucked the frets off with a pocket knife before coating the fingerboard with marine grade epoxy, I recommend using a fret puller. I did it the Jaco-way the first couple times around and it works, although it adds a little danger and increases potential damage to the fingerboard.

You don’t get extra points for doing it the hard way, it just takes longer.

You’re left with open slots that require filling. I’ve used “plastic wood,” epoxy and thin slices of wood, but of late my preference is super glue mixed with sawdust. From there I drilled out the plastic dot inlays, replacing them with walnut dowel. When finished this becomes nearly invisible. I also drilled out the side inlays and set new maple dots at the correct positions (without frets, the side dots mark the middle of where you need to play so you’d either be very flat or very sharp). Then I removed all finish from the play area of the neck. This is something you see in the violin family of instruments. A little oil and wax makes for a very smooth and playable neck. Other than an ebony string nut and some headstock work the neck is done.

THE BODY

“Why does it shake? The body… Why does it move? The fear…”

—Protomartyr, from The Agent Intellect “Why does it shake?”

“Why does it shake? The body… Why does it move? The fear…”

—Protomartyr, from The Agent Intellect “Why does it shake?”

The body was a bit unfamiliar. The main point of contemplation was on the sound hole. A feedback producer when amplified, I weighed a few options: removable cover, permanent patch or new top altogether. I went with a Spanish Cedar patch. I wish I could say it were seamless, but at the right angle you can pick out a square if you’re looking for it. It’s pretty hard to spot though.

The second thing keeping me awake at night was adding an additional 2” after the bridge allowing it to be strung with long scale strings. Being the most common scale, there are more options. At first I considered a tailpiece. My concern, which remains untested is that on a flattop bass guitar there would not be enough downward pressure on the bridge coming off a tailpiece. I’ve certainly seen this setup on 12- and 6-string flattop guitars, but I’m thinking the lighter strings allow for it.

I ended up creating a string block to sit under the bridge plate. The string block is African Mahogany with an Ebony cap which is accessed through an ebony back panel. This little bit of extra wood balances the guitar out better which was a happy bonus. This guitar weighs in at 5 1/2lbs—certainly a featherweight in the ring.

Comments